Ten things to know about affordable housing in Alberta

Ten things to know about affordable housing in Alberta

Here are 10 things to know about affordable housing in Alberta specifically:

- The NDP government of Rachel Notley undertook important initiatives pertaining to affordable housing. In its 2016 budget, the Notley government announced the near doubling of provincial spending on housing. This represented a total of $892 million in new funding, spanning a five-year period.

- According to the most recent Census, 11.4% of Alberta households experience core housing need, representing more than 164,000 households. In order to assess housing need for Canadians, the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation uses a measure called core housing need. A household is said to be in core housing need if, out of financial necessity, they either pay more than 30% of their gross household income on housing, live in housing requiring major repairs, or live in housing with insufficient bedrooms for the household size in question (as determined by the National Occupancy Standards).

- Seniors living alone in Alberta face particularly high rates of core housing need. Nearly 34% of senior (65+) females living alone in Alberta were in core housing need in 2011, while the figure for senior (65+) males living alone was just under 26%.

- Female lone-parent households in Alberta also face a particularly high rate of core housing need. More than 27% of these households were in core housing need in 2011. However, that figure likely dropped after the NDP government of Rachel Notley introduced the Alberta Child Benefit, a major feature of the 2016 Alberta budget.

- Members of Alberta First Nations also experience very high rates of core housing need. In fact, the rate of core housing need for Status Indians is nearly 25%—more than double the rate for non-Indigenous households in the province. And get this: these core need figures do not account for households living on reserve (if they did, that figure would be much greater). I should also note that more than 25% of persons experiencing absolute homelessness in Alberta identify as being Indigenous, even though Indigenous peoples make up just 7% of Alberta’s total population.

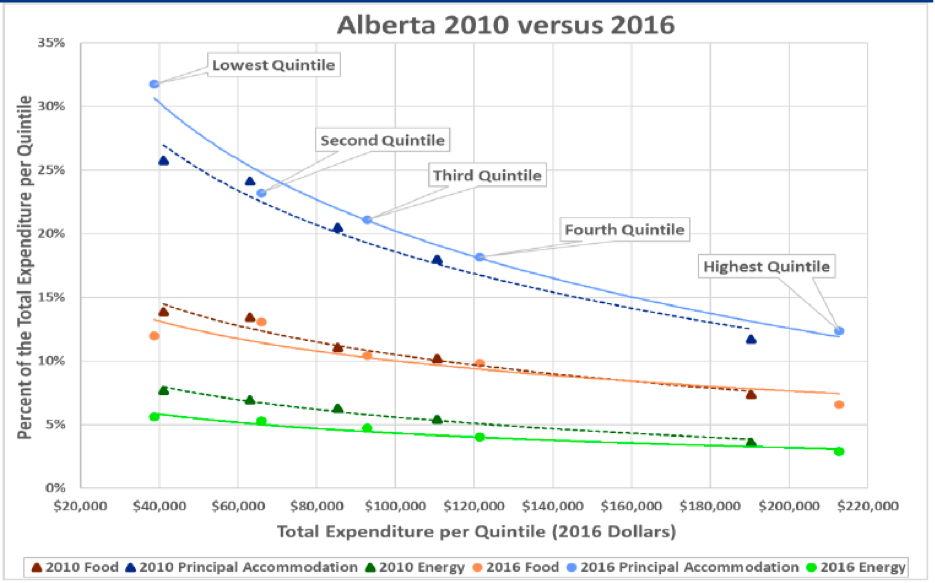

- Housing typically constitutes a larger share of spending for low-income households (compared with middle- and higher-income households). And as the figure below illustrates, that phenomenon got measurably worse for low-income households in Alberta between 2010 and 2016.

Source. Kneebone, R., & Wilkins, M. G. (2018). Social Policy Trends: Paying for the Essentials: Shelter, Food and Energy Consumption by Household Income Quintile for 2010 and 2016. The School of Public Policy Publications, 11. Retrieved from Policy School’s website: https://www.policyschool.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Social-Trends-Engel-Curves-July-2018.pdf

- On a per capita basis, Alberta has far fewer subsidized housing units than the rest of Canada. According to the most recent Census, subsidized housing represents just 2.9% of Alberta’s housing units; for Canada as a whole, the figure is 4.2%.

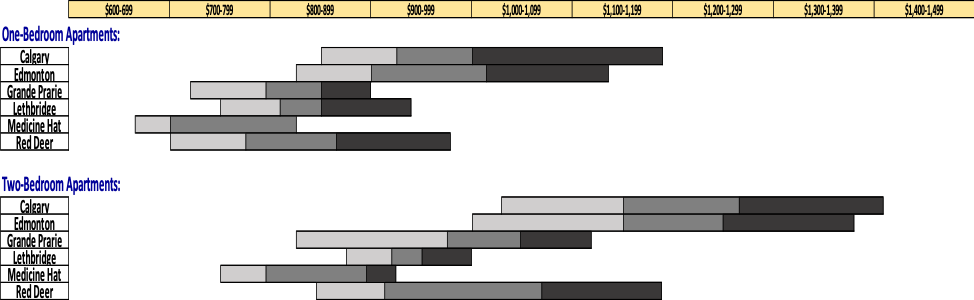

- Some Alberta cities have much more low-cost rental housing (per capita) than others. The visual below shows the range of private market rents paid on one- and two-bedroom apartments across Alberta’s seven major cities. The light-coloured bars show the range of rents paid on the second quintile (i.e., the second-poorest quintile) of private market rents. The next darkest bar shows the range of rents paid on the third quintile (i.e., the middle quintile) of rents, while the darkest bars define the range of rents paid on the fourth quintile of rents. Among the seven major cities, Medicine Hat appears to have the most low-cost rental housing units (per capita), and Calgary the fewest.

Notes. Monthly rent quintiles by city in 2017. Data provided to Ron Kneebone (University of Calgary) by Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. The range of rents paid on the first and fifth quintiles are not reported due to confidentiality reasons.

- Going forward, the impact of the federal government’s National Housing Strategy will be modest. Recent analysis by Canada’s Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO) projects future federal housing spending to actually decrease over the next decade (relative to Gross Domestic Product). The same analysis projects that total spending on Indigenous housing by Canada’s federal government will be “substantially lower” going forward. (For a general overview of the National Housing Strategy, see this analysis.)

- There are considerable cost savings to be realized when investing in affordable housing, especially when the tenants have serious mental health challenges. Subsidized housing for vulnerable subpopulations (including persons with mental health challenges) that is accompanied by professional staff support is referred to as supportive housing. Recent analysis in Calgary estimates considerable cost savings in the health and justice sectors attributable to formerly-homeless persons receiving supportive housing.

In Sum. For a more comprehensive look at affordable housing in Alberta, see this year’s Alberta Alternative Budget (AAB). Full disclosure: I was primary author of the chapter on affordable housing and homelessness.

I wish to thank the following individuals for invaluable assistance with the housing chapter of this year’s AAB: Meaghan Bell, John Kmech, Claire Noble, Chidom Otogwu, Steve Pomeroy, Ron Kneebone, Vincent St. Martin, John Veenstra and one anonymous reviewer. Any errors are mine.