Canada’s history of residential schools

Canada’s history of residential schools

When the school is on the reserve the child lives with its parents, who are savages; he is surrounded by savages…He is simply a savage who can read and write. It has been strongly pressed upon myself…that Indian children should be withdrawn as much as possible from the parental influence, and the only way to do that would be to put them in…schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.

— John A. Macdonald (Canada’s First Prime Minister)

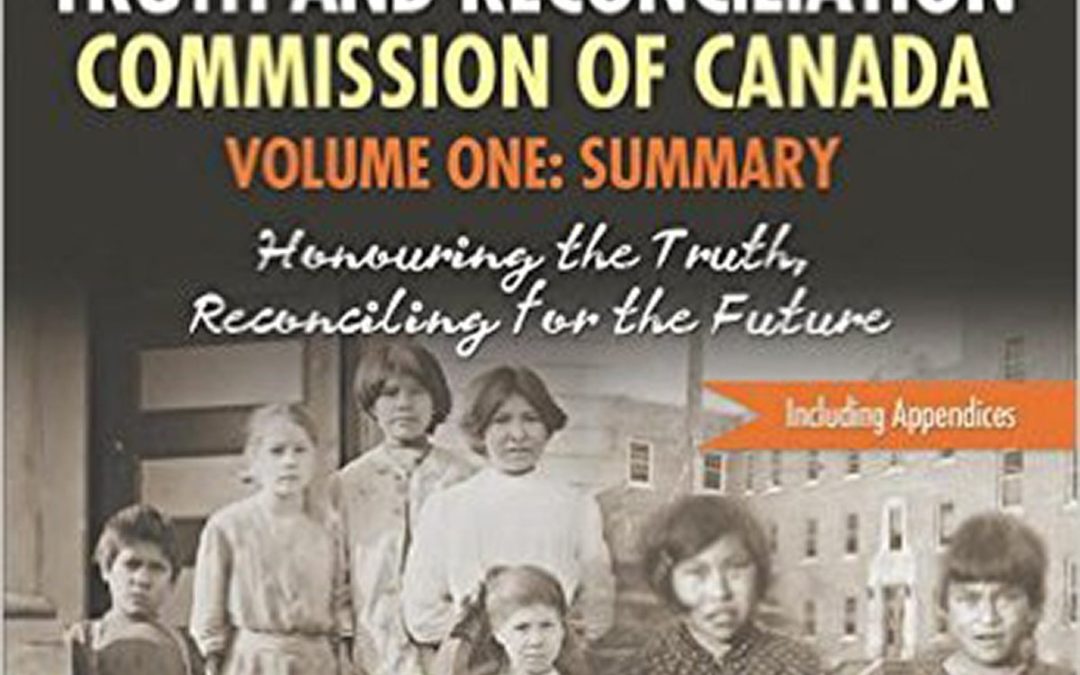

I recently had the chance to read the Volume 1 summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which discusses Canada’s history with residential schools.[1]

Here are 10 things to know.

1. Residential schools were part of a deliberate policy to assimilate Indigenous peoples against their will. Such schools existed in Canada for over a century, with federal support for them beginning in in the 1880s (peak enrolment was reached in the late 1950s). Federal officials hoped that students who went to these schools would stop feeling connected to their culture and would sever ties with their families and communities. Canada’s federal government used such schools to gain control over land and resources of Indigenous peoples.

2. Initially, attendance was voluntary; but this soon changed. It is also very important to bear in mind that many reserves did not have schools of their own, meaning that Indigenous people typically had no alternative to residential schools.

3. Residential schools were funded by the federal government, but administered by churches. The major religious denominations that administered Canada’s residential schools were: Roman Catholic, Anglican, United, Methodist, and Presbyterian. The Roman Catholic Church ran more of these schools than any other denomination. Most of the staff were recruited by the church. Each school’s principal was typically a priest or minister (as opposed to an educator). Staff were disproportionately women, many worked for free, and many worked seven-day weeks. Turnover was high—it was common for a staff person to work for a residential school for no more than two years before moving on to another job.

4. Residential schools were profoundly disruptive to families. Some students were sent to schools located several thousand kilometres from their communities; some went several years without seeing their parents. Siblings attending the same school were separated from each other.

5. Students were not allowed to speak Indigenous languages in residential schools. Often, they were physically punished when they tried. When students returned home, it was challenging for them to communicate with their parents, as well as discuss the abuse to which they were subjected in school. Only English—and French, to a lesser extent—were allowed to be spoken in residential schools.

6. Residential schools were woefully underfunded and used students as child labour. Prior to the early-1950s, students typically spent half the day in class, and the other half of the day working (e.g., growing much of the food they ate, fixing their own clothing). Not surprisingly, this resulted in a considerable number of workplace accidents (e.g., hands being caught in equipment). It also meant that students did not receive the same quality education as students in Canada’s mainstream schools.

7. Students at residential schools faced many forms of abuse. Students who wet their beds were often subjected to organized forms of public humiliation. One TRC witness testified that staff would line up the bedwetters and parade them through the dining hall at breakfast time in order to shame them. Sometimes students were forced to eat their own vomit.[2] One school even built its own electric chair. As is now well known, sexual abuse of Indigenous children was all too commonplace in the schools.

8. Not surprisingly, students often ran away from residential schools. Chanie Wenjack was an Anishinaabe boy who died in 1966 while trying to return home after escaping from a residential school. His story is now the subject of a multimedia art project, the centrepiece of which is Secret Path (the last studio album ever released by Gord Downie). And Trent University has the Chanie Wenjack School for Indigenous Studies. Hundreds of others ran away and died, and thousands died at school.

9. Parents often fought back. Sometimes they refused to enrol their students; sometimes they refused to return their children after they had run away from school and come home (or after summer holidays). Sometimes these tactics were effective, forcing some schools to close. Having said that, parents often faced legal sanctions (e.g., jail time) for employing such tactics. Parents also advocated for better conditions pertaining to pedagogy, food and clothing.

10. Beginning in the late 1940s, mainstream thought in Canada began to shift. Increasingly, public officials began to encourage the integration of First Nations students into the public school system. By 1960, more First Nations students were attending public schools than residential schools.

In closing. In the late-1960s, the federal government began to take control of residential schools away from churches. It then began to close them, with the last one closing in 1996. As of 2005, more than 18,000 lawsuits had been filed by residential school survivors against the federal government, churches and individuals. Despite the work of the TRC and the financial compensation, many Indigenous people are still experiencing intergenerational trauma from the experience of residential schools. The implications for homelessness have been studied extensively by Peter Menzies (see this book chapter, for example).

I wish to thank Frances Abele, Angele Alook, Kelly Black, Susan Falvo, Josh Gladstone, Root Gorelick, Katelyn Lucas, Jenny Morrow, Allan Moscovitch, and Vincent St-Martin for providing feedback on an early draft of this blog post. Any errors are mine.

[1] The TRC’s website is here, and all TRC reports can be found here.

[2] In 1999, a Roman Catholic nun was convicted of administering a noxious substance and assault (though she received no jail time).