Book review: Understanding spatial media

Book review: Understanding spatial media

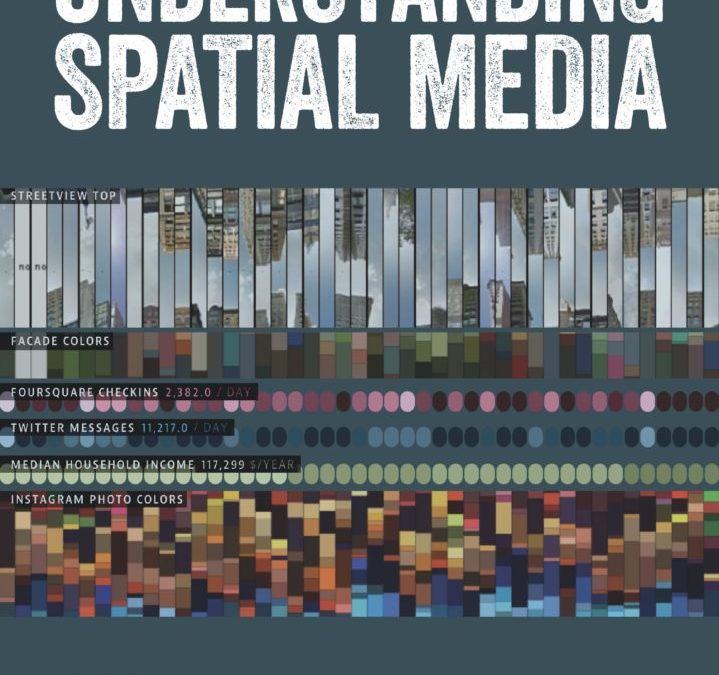

Rob Kitchin, Tracey Lauriault and Matthew Wilson recently co-edited a book titled Understanding Spatial Media. Published by SAGE, this book is about technology, power, people, democracy and geography.

Here are 10 things to know about the book.

1. The book can help us make better decisions pertaining to the acquisition and use of technology and data. Technological advancements happen quickly; this book encourages the reader to think carefully about these changes. It encourages us to think sociologically and technologically at the same time. That’s because technology isn’t neutral; there are politics and values embedded within it. We shape technology, which in turn shapes us.

2. This book matters because homelessness is inherently geographical. As an example, many households currently experiencing homelessness in Calgary used to live in First Nations communities. Understanding what’s driving their ‘flow in’ to Calgary’s Homeless-Serving System of Care is an important part of understanding homelessness in Calgary. Across Canada, rates of child poverty are much higher ‘on reserve’ than ‘off reserve.’ The visual below, taken from this report, makes that point quite clear.

3. The book is relevant to Point-in-Time (PiT) Counts of homelessness. Chapter 21 is about spatial profiling; it looks at the action of classifying people and then acting according to that classification. As noted by Calgary Homeless Foundation’s CEO, Diana Krecsy: “The language we use in PiT Counts gets translated into policy discussions.” For example, if communities choose to start counting veterans experiencing homelessness (as has happened in many Canadian communities over the past several years) it can translate into more attention being focused on the housing needs of veterans (which I would argue has also happened).[1] Indeed, categories and definitions used in PiT Counts are not value neutral.

4. Chapter 4, “Digitally Augmented Geographies,” highlights important differences in Internet accessibility globally. Authored by Mark Graham, I found this chapter very readable. Points raised in the chapter include the fact that approximately one-quarter of the world’s population “has still never used the internet” (p. 46). The chapter further notes that, of the approximately 3 billion people in the world who do use the Internet, “many are forced to use it in very restricted ways because of economic necessity (e.g. metered plans, bandwidth caps), technical limitations (e.g. slow connectivity speeds) and government restrictions (e.g. censorship or surveillance)” (p. 46). This is relevant for persons experiencing homelessness, and it’s especially relevant to northern regions of Canada; it’s also an important advocacy area for the Federation of Canadian Municipalities.[2]

5. Chapter 5, “Locative and Sousveillant Media,” discusses the use of smartphones to capture things on video…including things that weren’t intended to be captured on video. Readers learn that approximately two-thirds of the world’s population keeps a smartphone “within arms reach [sic] at all times, reaching for it 150 times per day…” (p. 57). The same chapter includes a discussion of people whipping out their phones and catching ‘incidents of interest’ on video—for me, this brought to mind a May 2017 incident in which a Toronto security guard was caught on camera while throwing objects at a man experiencing homelessness.

6. Chapter 7, titled “Urban Dashboards,” discusses a topic that is very relevant to my work at the Calgary Homeless Foundation (CHF). It notes that, since roughly 1990, the term “dashboard” has denoted “a screen giving a graphical summary of various types of information, typically used to give an overview of (part of) a business organization” (p. 75). It further notes: “Business and urban data displays often mimic the dashboard instrumentation of cards or aeroplanes. Where in a car you would find indicators for speed, oil and fuel levels, here you will find widgets representing an organization’s ‘key performance indicators’: cash flow, stocks, inventory and so forth” (p. 77). Below, readers can see an excerpt from a Calgary community dashboard.

This image is an excerpt from a Calgary community dashboard measuring collective impact on specific goals pertaining to homelessness to reach by the end of 2018.

7. Several of the book’s chapters are relevant to research currently being done at CHF. CHF is currently doing some ‘GIS mapping’ research. For clients receiving CHF-funded housing, we’re looking at the postal codes where they came from (before entering Calgary’s Homeless-Serving System of Care) as well as postal codes of the housing units where they end up (once we help house them). Similar research is discussed at various junctures of the book. The book’s co-editor, Dr. Tracey Lauriault, recently explained: “One of aims of the book in general is to give you the ‘critical thinking chops’ needed to do GIS mapping research.”

8. The book touches on many of the same issues discussed at the Canadian Homelessness Data Sharing Initiative. This annual event, co-hosted by CHF and the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, discusses infrastructure (i.e. where to store data); modeling and schemas (i.e. rules related to a classification system); analytics (i.e. the use of techniques, statistics and software), access to data, sensitivity (i.e. respecting people); linked data; and transparency. All of these topics are discussed in the book. (I’ve previously blogged about the inaugural data-sharing event here, and I’ve recently blogged about the second annual event here).

9. The authors who contributed to this book represent a diverse collection of scholars.Scholars from 18 universities, spanning six countries, participated in the effort. This is indicative of some impressive professional networking on the part of the book’s three editors—they opened a tent and let a lot of thinkers come inside it. This serves readers well.

10. This book is geared mostly to other researchers in geography and media studies. Most of the book’s intended readers are university professors and upper-level university students. I personally had great difficulty understanding several of the chapters. I even found Chapter 1 to be very difficult (it uses the words ontogenetic, neogeography, multivocal, geovisual and synoptic). I would therefore not recommend this book to people who lack prior knowledge in the realm of spatial media.

I wish to thank the following individuals for invaluable assistance with this blog post: Vicki Ballance, Rachel Campbell, Chantal Hansen, Patrick Hunter, Diana Krecsy, Tracey Lauriault, Kara Layher, Michael Lenczner, Lindsay Lenny and Joel Sinclair. Any errors are mine.

[1] For examples of recent attention to veterans’ homelessness in Canada, see this this Globe and Mail article and this PowerPoint presentation. (I suspect that a variety of factors, not just PIT Counts, have likely led to increased policy attention on veterans’ homelessness in Canada over the past several years.)

[2] You can download a “pre-publication version” of this chapter here, free of charge. You can check out Professor Graham’s web site here, and you can see his contributions to The Guardian here.

You can view a PDF version of this blog post here: Book review- Understanding spatial media