Supporting Indigenous residents at Horizon Housing

Supporting Indigenous residents at Horizon Housing

La version française de ce billet se trouve ici.

Horizon Housing is a non-profit affordable housing provider in Calgary that works in partnership with more than 40 community agencies that refer residents and provide ongoing social supports so residents can maintain stable housing over the long term.

Horizon recently commissioned a report with the view of improving housing outcomes for its Indigenous residents (i.e., residents who are First Nation, Métis or Inuit).

Here are 10 things to know.

1. One of Horizon’s desired outcomes is low rates of negative exits among its residents. A negative exit at Horizon is defined as an exit that happens for reasons other than a resident wishing to move, meaning it is involuntary on the part of the resident.

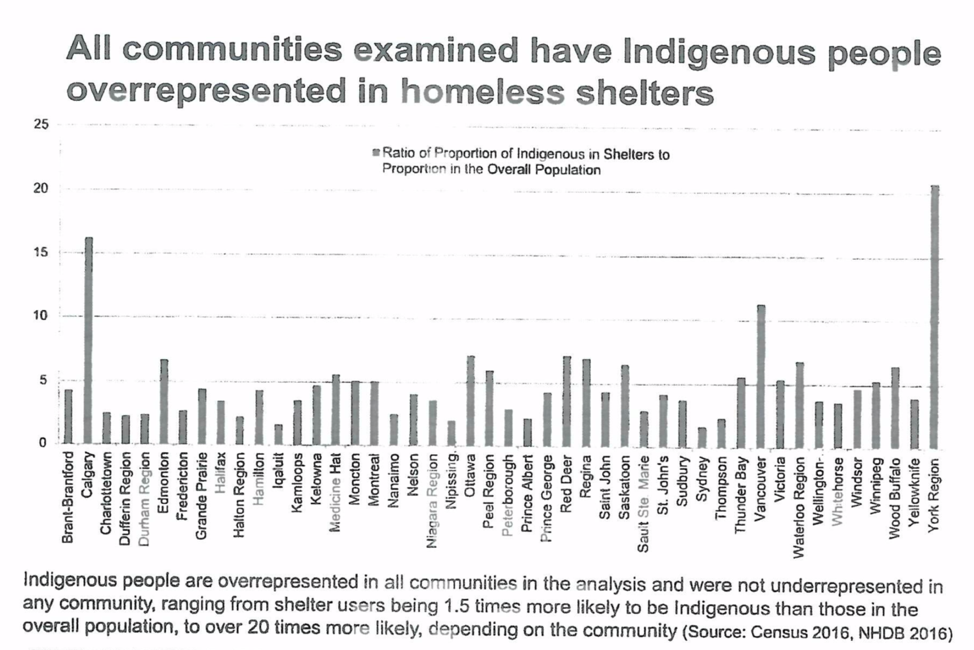

2. Indigenous residents at Horizon experience a disproportionate number of negative exits. While just over 10% of Horizon’s residents are Indigenous, 44% of Horizon’s negative exits concern Indigenous residents. More than three-quarters of negative exits experienced by Indigenous residents at Horizon involve a tenancy that lasts less than a year.

3. In 2020, Horizon reached out to Nick Falvo Consulting to explore the matter. The following methodological approaches were used: a literature review; interviews with Indigenous residents at Horizon; interviews with subject specialists; and focus groups.

4. An Advisory Committee met monthly to provide guidance to the research project. This committee’s membership consisted of four Indigenous people and two non-Indigenous people. They provided crucial guidance on protocol throughout the project, and reviewed drafts of all documents.

5. The report went through an extensive review process. This included the circulation of a draft version of the report to all research participants and several dozen experts across Canada. It also included four virtual presentations of draft findings, including one specifically for Elders.

6. The final report recommends more on-site cultural programming and access to Elders. A dominant theme raised by Indigenous residents was a desire to have Horizon organize cultural events in partnership with Indigenous-serving organizations. Such activities would be led by Elders.

7. It also recommends more opportunities to smudge. Several Indigenous residents expressed a strong desire to smudge, but were not sure whether they were allowed to smudge in their units, and were concerned that doing so might trigger smoke alarms or other concerns.

8. The report proposes an enhanced resident orientation process. Currently, resident orientation at Horizon is led by building managers. The report recommends an enhanced orientation that might consist of several stages, whereby incoming residents would feel more welcome and supported.

9. The report recommends that Horizon hire an Indigenous Liaison Person. Other terms for such a position include Indigenous Advisor and Cultural Resource Person. This person could help steward (i.e., ‘project manage’) Horizon’s Indigenous initiatives, track recommendations made in this report, and report on them regularly to meetings of Horizon’s Leadership Team, Horizon’s Board of Directors, and the community at large.

10. The report includes additional recommendations. These consist of: improved staff training; increasing the size of Horizon’s Resident Services Team (which provides front-line assistance to residents); Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design (an approach to building design whereby a law enforcement lens is applied to the built environment); the implementation of an eviction prevention initiative (whereby rent could be covered in the case of extenuating circumstances); Indigenous representation on Horizon’s Board of Directors and staff leadership team; and an annual survey specifically for Horizon’s Indigenous residents.

In sum. This report provides specific advice on how Horizon can work to improve housing outcomes for its Indigenous residents. Most of its recommendations are contingent on external funding, and all involve collaboration with Horizon’s partners—both existing partners and new partners. The report’s findings and recommendations may also be helpful to other housing providers across Canada.