A primer on supportive housing and Housing First

A primer on supportive housing and Housing First

La version française de ce billet se trouve ici.

On 3 February 2021, I gave a guest lecture in Greg Suttor‘s graduate seminar course at the University of Toronto’s Department of Geography and Planning (Greg is a long-time mentor of mine, so this was a huge honour). My presentation focused on how the worlds of housing and homelessness connect in Canada (and in Toronto especially).

My full slide deck, which contains considerable detail, can be found here.

Here are 10 things to know:

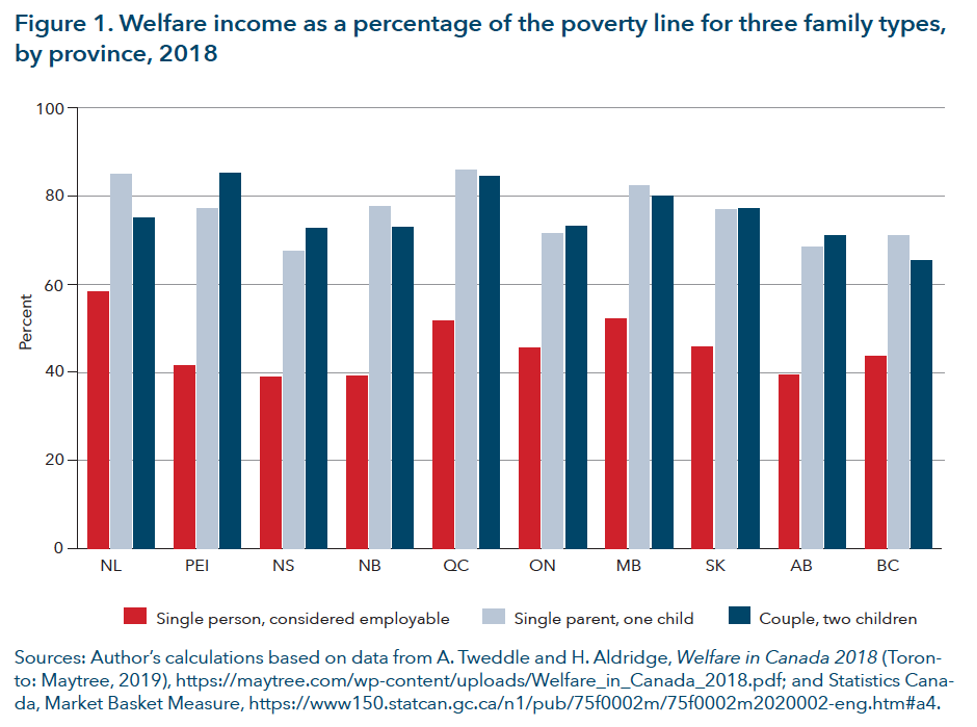

1. In Canada, most leading thinkers agree that subsidized housing is key to both preventing and responding to homelessness. However, there are important debates about: how much more subsidized housing is needed; who should be prioritized for the limited number of available units; which models of subsidized housing are best; and how much subsidy should be attached to each unit.

2. Elected officials do not agree on who should finance subsidized housing. Right now, there’s broad agreement that Canada’s federal government should provide assistance with up-front development costs (i.e., capital costs), but there’s considerable debate over who should finance the ongoing costs after the housing is developed (i.e., operating costs). This ongoing game of chicken, whereby one order of government waits for another one to cave, limits the amount of new affordable housing that gets created each year.

3. In Ontario, when homelessness emerged as a pressing public policy challenge in the 1980s, persons experiencing homelessness started to become a major focus of housing policy. An approach emerged at that time that focused on re-housing persons into subsidized housing and providing them with social work support. This approach became known as supportive housing (today, the term Housing First means almost the same thing). Most residents of supportive housing in Canada are single adults without dependants and are experiencing serious mental health challenges.

4. This didn’t happen in a political vacuum—indeed, political advocacy played a major role in bringing it about. In Toronto, this included the Singles Displaced Persons Project, the “consumer survivor” movement, the slogan “homes not hostels” and the founding of organizations such as Houselink Community Homes, and Homes First Society.

5. The type of social work support provided with supportive housing is the subject of much debate. When I provided such support while working in Toronto, I helped tenants keep track of appointments (e.g., doctors’ appointments, appointments with income support workers, and court appearances). I often accompanied tenants to the appointments. I advocated for them if they were ever being threatened with eviction and (when necessary) helped them relocate to new units. I frequently took them for coffee as well.

6. Place-based supportive housing makes it relatively easy to organize group social activities. Place-based supportive housing refers to a situation where an entire building is occupied by tenants in need of supportive housing (as opposed to just a small percentage of a building’s units being occupied by a specific population group). This type of supportive housing typically involves on-site staff support (with some models, there are staff on site at all times). Place-based supportive housing can offer important assistance with guest management and makes it relatively easy to have meal programs, as well as exercise and art classes.

7. In Canada, Housing First—which means something very similar to supportive housing—became an effective narrative beginning in the early 2000s. The City of Toronto pushed this hard beginning in 2005, and the Calgary Homeless Foundation picked it up quickly as well; advocates and practitioners across Canada now use the term extensively. The Housing First narrative places great emphasis on the importance of not requiring housing readiness on the part of the prospective tenant as a condition of obtaining housing.

8. Ideologically, advocacy in favour of Housing First isn’t exactly left or right; rather, it entails a ‘third way’ political advocacy strategy. Largely because of that ‘third way’ approach, it has found traction among business leaders, elected officials of all stripes and a broad cross-section of advocates. Part of this stems from the fact that Housing First advocates often promote a reallocation of existing resources. It also stems from the fact that Housing First proponents tend to favour the use of housing owned by for-profit landlords (whereas proponents of supportive housing have historically favoured non-profit ownership).

9. Housing First was further advanced by Canada’s At Home/Chez Soi study. This was a five-city randomized controlled study in which participants with moderate needs received Intensive Case Management, while those with higher levels of need received Assertive Community Treatment. Participants were interviewed every three months over two years. Results demonstrated successful outcomes and cost savings.

10. Canada’s National Housing Strategy, unveiled in 2017, contains no specific provisions for supportive housing and makes no mention of Housing First. Yet, the September 2020 Federal Throne Speech includes a commitment to “completely eliminate chronic homelessness.” Further, just 5% of new funding under the National Housing Strategy has been earmarked towards the goal of reducing chronic homelessness.

In sum. The good news is that most of Canada’s thought leaders believe that supportive housing—often articulated via Housing First language—is an important way to both prevent and respond to homelessness. The bad news is that most elected officials are reluctant to commit the necessary funding to substantially reduce homelessness—for example, the National Housing Strategy appears insufficiently resourced to meet the Government of Canada’s objective of ending chronic homelessness.

I wish to thank Damian Collins, Stéphan Corriveau, John Ecker, Joshua Evans, George Fallis, Susan Falvo, Hayley Gislason, David Hulchanski, Michel Laforge, Steve Lurie, Geoffrey Nelson, Deborah Padgett, Angela Regnier, John Rook and Vincent St-Martin for assistance with this blog post. I also wish to thank HomeSpace Society for permission to use the photo used in this post.