Affordable housing and homelessness in Helsinki, Finland

Affordable housing and homelessness in Helsinki, Finland

La version française de ce billet se trouve ici.

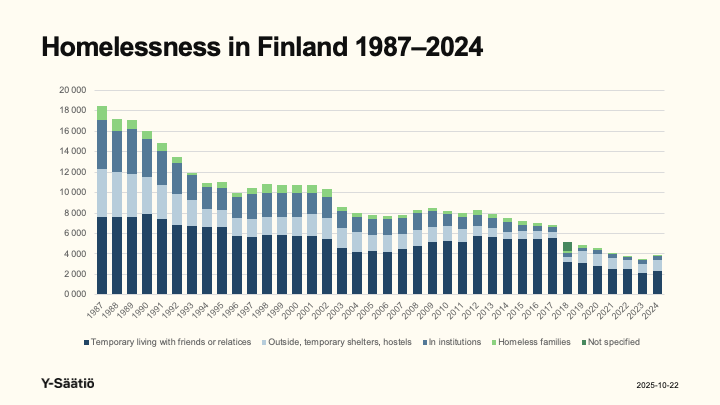

I recently organized a study tour of Helsinki, in partnership with the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association and the Chartered Institute of Housing Canada. Its focus was on affordable housing and homelessness in a country that has almost completely eliminated absolute homelessness (see visual below). My summary notes from the tour are available here.

Here are 10 things to know:

1. Finland has robust public social spending. Public social spending in Finland represents 29% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). The OECD average is 21.1%, while the figure for Canada is 24.9% (all of these figures are available here). Such social spending allows Finland to invest in a broad suite of social programming—both directly and indirectly related to homelessness—that can both prevent and manage homelessness.

2. Finland also has higher taxation than many other countries. Finland’s tax-to-GDP ratio is 42.4%. The OECD average is 33.9%, while the Canadian figure is 34.8% (these figures are available here). Such taxation helps finance Finland’s high rates of public social spending.

3. On a per-capita basis, Finland has considerably more community (i.e., social) housing than do most other countries. In Finland, 10.9% of housing is ‘social renting.’ The OECD average is 7.1%, while the Canadian figure is 3.5%—meaning that Finland’s rate of social renting is more than three times higher than Canada’s (all of these figures are available here). A key advantage of community housing is that it tends to keep rent levels low over the long term.

4. On the demand side, Finland has relatively generous housing allowances (which help renters afford rent). Finland spends considerably more than most OECD countries on housing allowances (in relation to GDP). Canada spends considerably less.[1] This helps low-income households afford rent in both private and community housing. In Finland, it’s an entitlement program, meaning there’s no waiting list for households who meet the eligibility criteria.

5. Even with strong public social spending, homelessness can persist. This helps us understand how Finland has seen considerable amounts of homelessness at various junctures in its history (see visual above).

6. Finland saw a significant and steady reduction in homelessness from the late 1980s until the mid 1990s. Two factors led to this:

i) A massive wave of subsidized housing construction that resulted in tens of thousands of new, permanently affordable apartments built every year often targeted to low-income households; and

ii) A national effort to reduce homelessness (introduced in 1987) requiring municipalities to take greater responsibility for ensuring housing for vulnerable groups, including people experiencing homelessness. This meant cities like Helsinki purchased and allocated apartments specifically for people experiencing homelessness.

7. Beginning in 2007, Finland gained further traction in the fight against homelessness. A new Finnish housing minister (from a right-of-centre political party) began to lead a new approach in 2007. The following year, Housing First was introduced in Finland, and there was considerable new investment in supportive housing. In the words of Juha Kahila: “We went all in. No pilot programs. No pilot cities.” This involved a lot of training for front-line staff as well.

8. Exits from public systems into homelessness can be a challenge in Finland. The good news is that discharges from child protection into homelessness don’t happen at all. Discharges from hospitals into homelessness do happen but are rare. Sadly, discharges from jail into homelessness do happen (and this is a shortcoming of the Finnish system).

9. Many of Helsinki’s community housing providers offer supported employment opportunities for their tenants. Keeping in mind that many tenants have serious health challenges, ‘low-threshold work activities’ are common. They include cleaning, snow shoveling, and basic maintenance. This activity pays the tenant 2 Euros per hour, up to four hours a day (so 8 Euros per day). Workers are paid in cash, twice a week. This does not negatively affect their income assistance eligibility.

10. Not everything with respect to homelessness in Helsinki is peachy at the moment. In addition to challenges associated with discharges from jail into homelessness, Helsinki is very much affected by the arrival of a relatively new designer drug: Alpha PHP. And open drug dealing and open drug use have both become much more prevalent in the past 2-3 years (mostly smoking, but there is some injection drug use as well). Finally, a relatively new national government has begun making cuts to important social welfare programs, and this helps explain a recent uptick in homelessness.

In sum. Finland’s history with homelessness suggests that intentional programming and targeted spending in the context of robust public social spending can lead to substantial drops in homelessness.

I wish to thank Juha Kahila, Jenny Morrow, and Annick Torfs for assistance with this blog post.

[1] Figures for Finland are available here. For Canadian figures, you can read Greg Suttor’s analysis here (see endnote #93).