The use of homeless shelters by Indigenous peoples in Canada

The use of homeless shelters by Indigenous peoples in Canada

Here are 10 things to know:

- The analysis draws on data gathered from homeless shelters across Canada. ESDC has data on persons using homeless shelters from roughly half of the country’s homeless shelters. This includes data gathered via the Homeless Individuals and Families Information System (HIFIS) software, as well as data gathered via data sharing agreements with the City of Toronto, the Government of Alberta and BC Housing. The data used for this analysis was gathered in 2016 and is based on approximately 133,000 unique individuals (approximately 41,000 of whom are Indigenous).

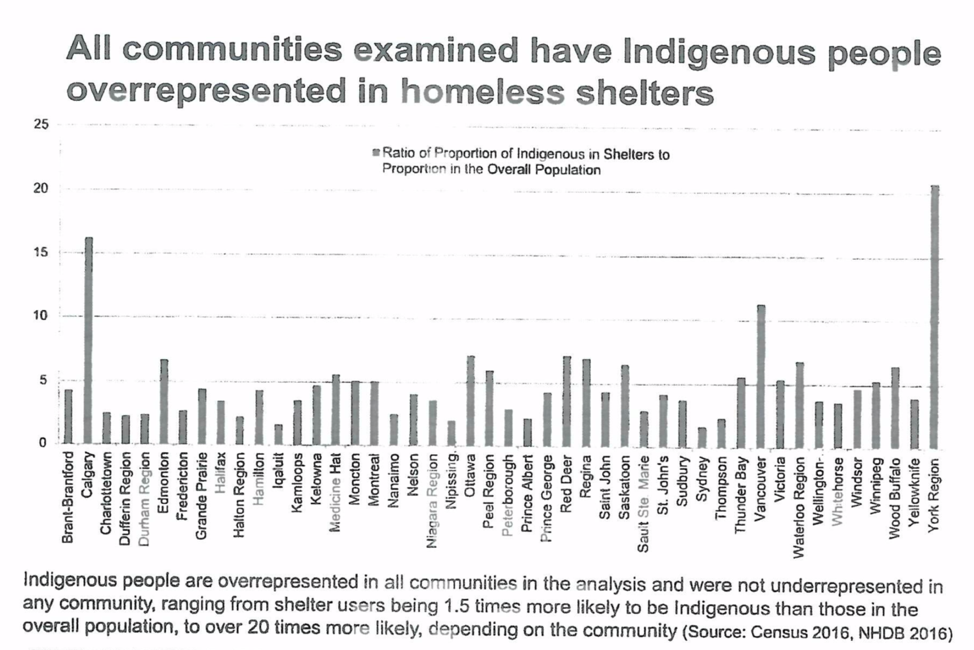

- According to the slide presentation, Indigenous peoples in Canada are more than 11 times more likely to use a homeless shelter than non-Indigenous people. Results of the analysis are succinctly summarized in a memo prepared for the Minister which accompanies the slide presentation: “Results show that Indigenous peoples are consistently overrepresented in homeless shelters in all 46 communities examined [Indigenous peoples accounted for more than 30% of people using homeless shelters over the course of 2016, while representing less than 5% of the total population]…The degree of overrepresentation is particularly high for Indigenous women, seniors, and Inuit. Indigenous shelter users experience more shelter stays each year, and are less likely to exit a shelter because of finding a residence.”

- As noted in the accompanying memo: “A report is being written to expand on the results shown in the deck.” Neither the memo nor the slide presentation indicate when the report will be ready, which people and groups will be invited to provide input on drafts of the report, or whether the report will be made public. Put differently, the federal government seems to be holding its cards close to its chest on this.

- I was personally surprised to see the extent to which Indigenous peoples experience high episodic shelter use. In other words, Indigenous peoples (compared with non-Indigenous peoples) tend to cycle in and out of shelters with high frequency, rather than stay for long periods of time.[1]

- I find it remarkable that these very important research findings had to be obtained via an ATIP request. In light of the federal government’s stated commitment to reconciliation, I would have thought it would have proactively released these findings and engaged Indigenous stakeholders in the process. This raises the following questions: To what extent were Indigenous peoples part of this analysis (beyond the fact that their data was collected and analyzed)? To what extent will Indigenous peoples be invited to discuss the implications of the analysis? Why does the slide presentation make no mention of the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association’s Indigenous Caucus?

- The findings pertaining to shorter shelter stays raise at least two questions. First, why do Indigenous peoples have short, but frequent, stays in homeless shelters? Second, what could be done to address this? Frequent migration between urban centres and First Nations communities may help explain this. This may also speak to the need for more low-barrier and culturally-appropriate housing options in Canada—both emergency and permanent options.

- The findings showing Inuit over-representation are disturbing, though not surprising. Canada’s Inuit experience high rates of unemployment, poverty, and housing need. For more on this, see: the Inuit Statistical Profile 2018, published by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami; this Statistics Canada report from 2018; and this profile of Inuit living in Ottawa.

- The findings pertaining to women and seniors merit reflection. The analysis finds that, while Indigenous men are more than 10 times more likely to use a homeless shelter over the course of a year than non-Indigenous men, Indigenous women are more than 15 times more likely to use a homeless shelter than non-Indigenous women over the course of a year. Meanwhile, Indigenous seniors are more than 16 times more likely to use a homeless shelter over the course of a year than non-Indigenous seniors. Why would rates of Indigenous over-representation in Canada’s homeless shelters be higher for women and seniors than for other categories?

- I was disappointed to see Canada’s largest city dropped from the analysis. According to the slide presentation, City of Toronto data could not be included in the analysis because the City of Toronto lacked Indigenous status data for more than 40% of unique individuals using its homeless shelters. I hope it serves as wake-up call to the Toronto’s homeless-serving sector.

- Among the communities studied, Calgary’s rate of Indigenous over-representation was especially high (see screenshot below). The analysis found that, in Calgary, shelter users are about 16 times more likely to be Indigenous than are members of the city’s total population. The rate for Edmonton appears to be about half of that, with only York Region (near Toronto) having a higher rate among the cities studied. It is worth noting that the Calgary Homeless Foundation recently commissioned a research project assessing flow between Treaty 7 First Nations and Calgary’s Homeless-Serving System of Care. Hopefully that project can shed light on this matter. (Full disclosure: I’m one of the research consultants working on this project, along with Gabrielle Lindstrom, Steve Pomeroy, and Jodi Bruhn.)

The following individuals provided me with assistance in preparing this blog post: Jodi Bruhn, Kathy Christiansen, Damian Collins, Dan Dutton, Ron Kneebone, Diana Krecsy, Eric Latimer, Katelyn Lucas, Jenny Morrow, Jennifer Robson, Vincent St-Martin, and two anonymous reviewers. Any errors are mine.

[1] Federal definitions of chronic vs. episodic homelessness are available here.