The long-term impact of the COVID-19 Recession on homelessness in Canada

The long-term impact of the COVID-19 Recession on homelessness in Canada

La version française de ce billet se trouve ici.

I’ve written a report for Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) that assesses the likely long-term impact of the current recession on homelessness. The link to the report is here.

Here are 10 things to know:

1. The current recession may contribute to rising homelessness across Canada, but that matter is complicated by several factors. Those factors include: a lag effect of up to five years from the time a recession starts until its impact fully plays out; the many unknowns that lie ahead (e.g., whether there will be future waves of the pandemic, when and if a vaccine is developed, what types of new social benefits are announced, etc.); and differences from one community to another (with respect to both the labour market and housing market, for example).

2. A recession’s lag effect stems in part from a strong desire of households to avoid absolute homelessness. When faced with reduced income or outright job loss, a household may try to arrange a rental arrears plan with their landlord; they may also borrow money from family and friends. They may try to move into cheaper housing as well, or move in with family or friends. The lag effect also stems from Canada’s elaborate social welfare system. For example, Employment Insurance (and more recently the Canada Emergency Response Benefit) can cushion the blow from job loss and help households hang on to their housing. Social assistance, while not as generous, can also delay homelessness onset.

3. This lag effect means there is time for senior orders of government to plan homelessness prevention initiatives. Since it could be a few years before we see rising homelessness in some communities as a result of the current recession, there is time for preventive measures to be designed, implemented and to take effect. Those measures could target households that are either at serious risk of becoming homeless or that have just become homeless.[1]

4. The recession’s impact on homelessness will vary from one community to another. Housing markets, income assistance systems and homelessness system planning frameworks vary across Canada. What is more, migration patterns over the next several years will be hard to predict. As a result, it is challenging to say which Canadian communities will see rising homelessness at what junctures in time. We do know that, thus far, the following types of workers in Canada have been most directly affected by the COVID-19 Recession: young people, women, nonmarried persons, and persons without high school accreditation.

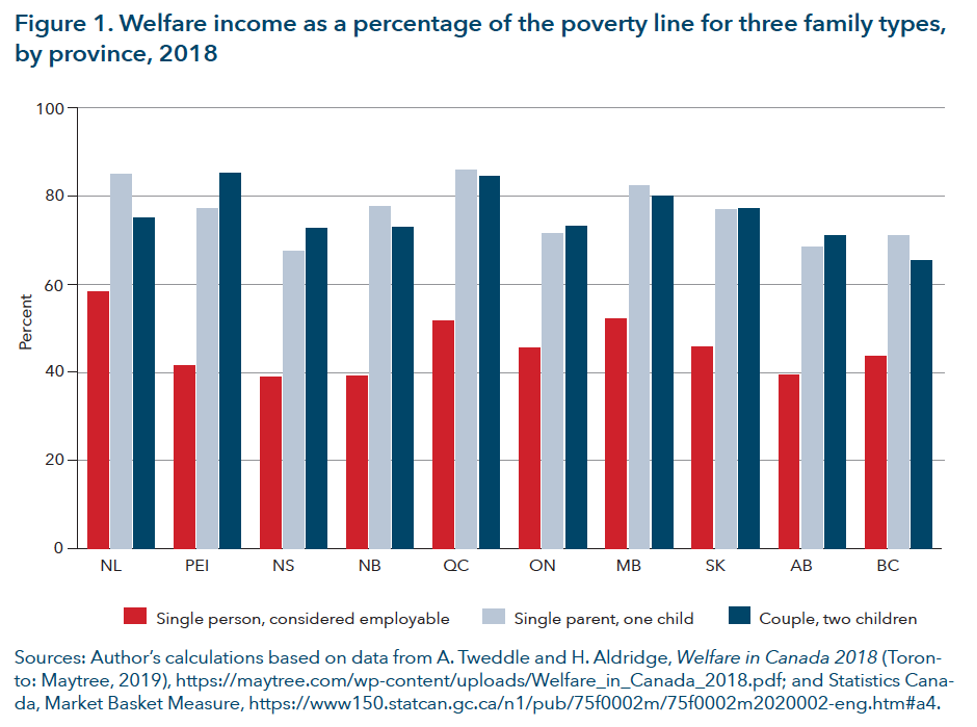

5. In order to monitor the many complex factors involved here, policy-makers needs to track various indicators. The report recommends that ESDC track the following indicators as the recession unfolds: the official unemployment rate; the percentage of Canadians falling below the Market Basket Measure (and especially those falling below 75% of the Market Basket Measure);[2] social assistance benefit levels; median rent levels; the rental vacancy rate; the percentage of households with extreme shelter cost burdens; evictions; and average nightly occupancy in emergency shelters.

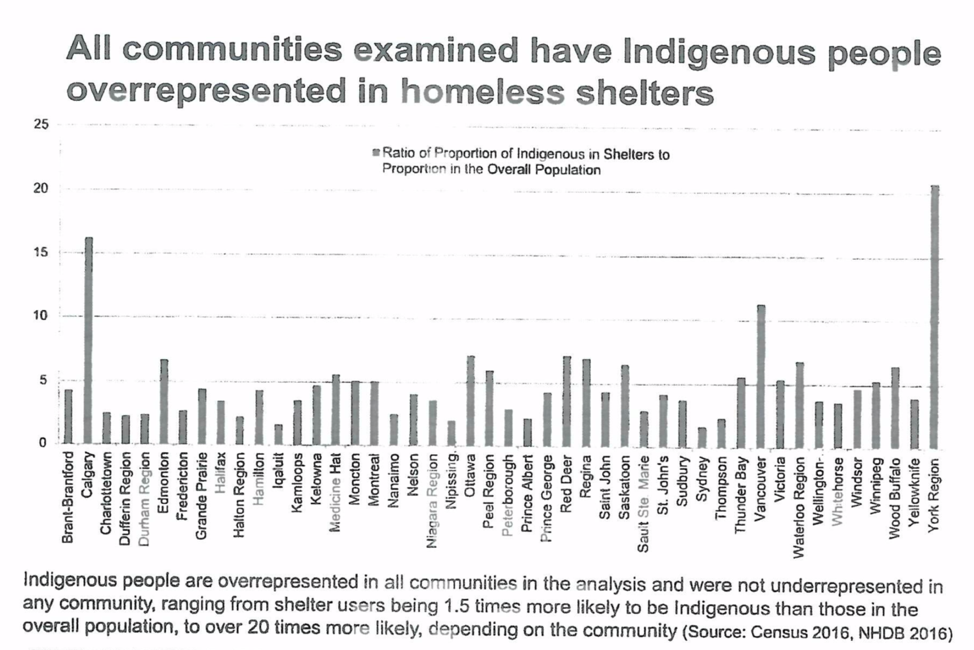

6. This tracking will require some nuance. As much as possible, such tracking should emphasize both how these indicators have changed since the start of the pandemic, and how this change varies across both geographical areas and specific populations (e.g., women, youth, Indigenous peoples, etc.).

7. The report recommends that the federal government enhance the Canada Housing Benefit (CHB). This benefit provides financial assistance to help low-income households afford rent. It is expected that half of this money will come from the federal government, and the other half from provinces and territories. The CHB was supposed to launch nationally on 1 April 2020; however, just five provinces have formally agreed to terms regarding the CHB. The federal government could increase the value of this benefit, which could encourage other provinces and territories to sign on. For example, the federal government might offer 2/3 or 3/4 cost-sharing.

8. The report also recommends that the federal government take a soft approach to recovering CERB overpayments from social assistance recipients. This is important in light of the considerable confusion that existed as the CERB was being rolled out. Such an approach might include not trying to fully recover the value of the CERB from these individuals (via the tax system). Even complete amnesty should be considered in some cases.

9. The report recommends that ESDC introduce a new funding stream for Reaching Home (i.e., the federal government’s main funding vehicle for homelessness). The report discusses the successful implementation of prevention efforts in the United States following the 2008-2009 Recession, and encourages ESDC to introduce something similar for Canada. A new prevention stream could focus on time-limited financial assistance directed at households who are either still housed (but at risk of becoming homeless), are in the process of losing their housing, or who have just begun to experience absolute homelessness. Targeting can evolve over time, in light of changes seen in the aforementioned indicators (e.g., the official unemployment rate, the percentage of persons with incomes below the Market Basket Measure, etc.).

10. The report identifies policy changes that could be made by provincial and territorial governments. These include increases to social assistance benefit levels, the reinstatement of social assistance eligibility for recipients who became ineligible due to the CERB, and the encouragement of housing-focused practices at emergency shelters.

In sum. Since we know there is serious risk for more homelessness in Canada as a result of the current recession, senior orders of government need to limit the damage. Well-designed prevention efforts can be more cost-effective than emergency responses after the fact.

I wish to thank Susan Falvo and Vincent St-Martin for assistance with this blog post.

[1] It is also very important to continue addressing existing homelessness. I’ve written about that here.

[2] For more on the Market Basket Measure, see this blog post.