This afternoon I gave a presentation at Raising the Roof’s Child & Family Homelessness Stakeholder Summit in Toronto. My slide deck can be downloaded here. To accompany the presentation, I’ve prepared the following list of Ten Things to Know About Homelessness in Canada.

1.Efforts to enumerate persons experiencing homeless have generally been spotty, but it is reasonable to assert that homelessness in Canada saw substantial growth in the 1980s and 1990s. On a nightly basis in Toronto, there were about 1,000 persons per night staying in emergency shelters in 1980. By 1990, that figure had doubled. And ten years later, there were 4,000 persons per night staying in Toronto’s emergency shelters. The Toronto figure of 4,000 per night has remained relatively constant for the past 15 years, though it has edged up in the aftermath of the 2008-2009 recession a phenomenon which I’ve previously written about here. (Admittedly, the number of persons living in emergency shelters on a nightly basis is a rather narrow gauge of homelessness. According to Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, approximately 13% of Canadian households are in core housing need; for Nunavut, the figure is a whopping 39%.)

2. Though it’s difficult to establish causation, I think relatively safe assumptions can be made about some of the major contributors to homelessness. Researchers are generally careful about using the term causation in fact, there are long-standing tensions among academic disciplines as to what methodological approaches are required to establish it. Statisticians, for example, generally believe that randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are needed to establish causation; but as David Freedman has argued, RCTs are often impractical or unethical (Freedman, 1999, p. 255). Rather, careful researchers are more likely to say things like these factors have likely contributed to this effect,” or “I think it’s likely that this effect caused this to happen And with that in mind, I’d like to suggest that there are probably three major factors that have contributed to homelessness in Canada: 1) macroeconomic factors (especially unemployment); 2) changes to our social welfare system (including a decrease in the availability of government-subsidized housing); and 3) the design and administration of policies whose specific intent is to respond directly to homelessness (often referred to as ‘systems responses’ to homelessness).

3. Homelessness has profound ramifications on the lives of children. As I wrote in 2012: Two studies have been done in Toronto looking at the role of housing with respect to children in care. Results of both studies indicate that the state of the family housing was a factor in one in five cases in which a child was temporarily admitted into care. Results from the Toronto research also indicate that, in one in 10 cases, housing status delayed the return home of a child from care (Falvo, 2012, p. 14). Other research estimates that, on an annual basis in Toronto alone, approximately 300 babies are born to mothers who are homeless. (Of course, homelessness can have profound ramifications on the lives of adults as well. For more on this, see this 2007 study.)

4. The role of Canada’s federal government in funding both housing for low-income persons and programming for homeless persons has varied considerably over time. Provinces and territories spend much more of their own money on housing for low-income persons when the federal government leads. Thus, a considerable amount of subsidized housing for low-income Canadians was built from the mid-1960s through to the early 1990s. Since the early 1990s, comparatively little subsidized housing has been built for low-income persons in Canada. I should also note that the annual, inflation-adjusted value of federal funding for homelessness today is worth just 35% of what it was worth in 1999.

5. Not every province/territory responds to homelessness in the same way. While much mores subsidized housing for low-income persons gets built when the federal government leads, provinces and territories don’t always respond to federal funding initiatives in the same way. For example, between 2002 and 2013, three times as many subsidized housing units were built in Alberta (on a per capita basis) than in Ontario. I would argue that a driving force behind this differential stems from Alberta’s strong economic performance during this same period relative to that of Ontario’s.

6. Though a careful researcher will be cautious in discussing what causes homelessness, I think we know a lot about what solves it. In many cases, a person who stays in an emergency shelter will exit homelessness without substantial public resources. In some cases, they might find housing on their own; in other cases, family and friends may provide them with short term assistance e.g. some financial support, a couch to sleep on, etc. (To learn more about lengths of stay in homeless shelters in a sample of Canadian cities, see this 2013 study.) Researchers and advocates for the homeless generally don’t view such short-term stays as a major public policy challenge the bigger challenge is in the case of persons who stay in emergency shelters (and outside) for longer periods of time. Even here though, I would argue that it’s hardly a mystery as to what constitutes an effective policy response.

Indeed, as early as the mid-1980s, small non-profit organizations in Ontario (and possibly in other provinces as well) found success in building subsidized housing for persons who had experienced long-term homelessness they did so by providing professional staff support to help such tenants live independently in those units. This was (and still is) known as supportive housing. The emergence of supportive housing in Ontario happened in large part due to strong advocacy by community-based groups. This included: the Singles Displaced Persons Project; the consumer/survivor movement; the slogan homes not hostels the founding of Houselink Community Homes; and the founding of Homes First Society. Conditions of eligibility for such housing varied from one provider to the next. In many cases, the tenant did not have to prove housing readiness before being offered a unit. In fact, Homes First Society got its name because its founders believed that its tenants needed homes first before addressing other challenges (i.e. mental health, substance use, employment, etc.).

Today, researchers, practitioners and advocates refer to this approach ashousing first. And very recently, a successful RCT of housing first was conducted in five Canadian cities; I’ve previously written about that study here.

7. There are several ways of making housing available to low-income households; all of them involve the private sector to varying degrees. Sometimes when government subsidizes housing for low-income persons, it provides money to a non-profit entity that develops, owns and operates the units. Other times, government provides a subsidy to landlords (either for-profit or non-profit); in exchange for the subsidy, the landlord agree to rent units at a reduced rate for a specified period of time (e.g. in some cases, for 10 years). And other times, government provides money (often known as a housing allowance) to low-income tenants who then rent a unit from a for-profit landlord. Of the three possible approaches, I personally have a preference for the option where a non-profit entity develops, owns and operates the units (and I have previously written about this here). Having said that, I think there’s a place for all three approaches, depending on local context.

8. Some jurisdictions have used sophisticated information management systems as part of their efforts to respond to homelessness. Many organizations serving homeless persons in Calgary enter client information into a database called the Homelessness Management Information System, a system that is also used in many American cities. Client-level information (such as age, health status, employment status and housing status) is entered into the database when an initial intake is done. While the client is receiving services, updated information is entered again; in the case of some programs, follow-up assessments are done every three months. In the case of some program types, there are both exit and post-exit follow-up assessments completed. All information-gathering is subject to provincial privacy legislation. There are many uses for the data once it’s gathered. For example, some organizations use the data to provide case management services to clients. Also, funders are able to assess each organization’s performance against benchmarks (i.e. percentage of clients who receive housing after a specific period of time).

9. When it comes to both preventing and responding to homelessness, the capacity of government to generate revenue matters a great deal.Governments typically use revenue generated from taxation to finance both subsidized housing and other important social programs. When tax revenue decreases, many governments have less ability to spend on such programs. Since the mid-1990s, tax revenue in Canada (measured as a percentage of our Gross Domestic Product) has decreased substantially. If this trend doesn’t reverse itself soon, it will be very challenging for many governments (especially provincial, territorial and municipal governments) to invest in important social programs. There is currently a move afoot by some Canadians to increase taxes; it is led by Alex Himelfarb, former Clerk of the Privy Council. Alex and his son Jordan recently co-edited a book that calls for the need for higher taxation in Canada. (Note: according to some schools of thought, it isn’t necessary for a sovereign government with its own currency to tax more in order to finance more social spending. While keeping in mind that such an approach would be most relevant to Canada’s federal government and much less relevant to provincial, territorial and municipal governments readers can read more about one such school of thought here.)

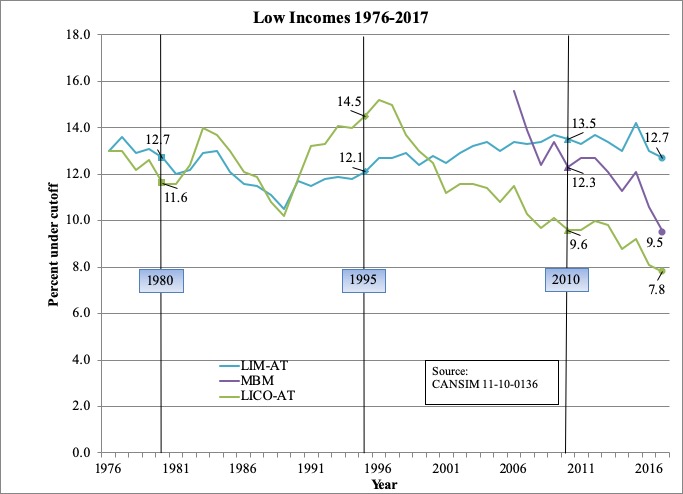

10. Over the course of the next decade, Canada will likely see substantial increases in homelessness among both seniors and Indigenous peoples (First Nation, Metis and Inuit). Seniors and Indigenous peoples are growing as a percentage of Canada’s total population. Further, the percentage of seniors living below Statistics Canada’s Low-Income Measure has grown substantially since the mid-1990s. I think all of this makes it likely that both of these groups will begin to grow as a percentage of Canada’s homeless populations.

–

The following individuals were very helpful in helping me prepare the present blog post: Maroine Bendaoud, Lisa Burke, George Fallis, Greg Suttor, Francesco Falvo, Louise Gallagher, Ali Jadidzadeh, Lisa Ker, Jennifer Legate, Kevin McNichol, Richard Shillington, Blake Thomas and Mike Veall. Any errors are mine.