Les effets à long terme de la récession de la COVID-19 sur le sans-abrisme au Canada

Les effets à long terme de la récession de la COVID-19 sur le sans-abrisme au Canada

An English-language version of this blog post is available here.

J’ai rédigé un rapport pour Emploi et Développement social Canada qui présente les impacts les plus probables de la récession actuelle sur le sans-abrisme. Le rapport complet est disponible (en anglais) ici.

Voici 10 choses à savoir à ce sujet.

- La récession actuelle risque de contribuer au sans-abrisme au Canada, mais plusieurs facteurs influenceront son ampleur. Parmi ceux-ci : le ressentiment des effets de la récession pourrait prendre jusqu’à cinq ans; les nombreux inconnus à l’horizon (par exemple, de potentielles vagues subséquentes de la pandémie, le développement d’un vaccin, la nature de futures prestations); les variantes démographiques d’une communauté à l’autre (notamment en ce qui concerne le marché du travail et le marché immobilier).

- L’effet de décalage de cinq ans s’explique en partie par la lutte pour éviter de perdre leur logement. Lorsque les ménages affronteront une perte de revenu ou d’emploi, ils pourraient tenter de négocier des arriérés de loyer avec le propriétaire de leur domicile; ils pourraient aussi emprunter de l’argent à des amis ou à d’autres membres de leur famille. Ils pourraient tenter d’emménager avec des amis, de la famille, ou dans un logement plus abordable. Le système de bienêtre social canadien a également pour effet de retarder les effets de la récession. Par exemple, les prestations d’assurance emploi (et plus récemment la Prestation d’urgence canadienne) peuvent atténuer les effets d’une perte d’emploi, aidant ainsi les ménages à maintenir leurs logements. Même si elle est moins généreuse, l’assurance sociale peut également contribuer à retarder le sans-abrisme.

- L’effet de décalage donne aussi la chance aux paliers gouvernementaux supérieurs de prévoir des initiatives contre le sans-abrisme. Puisqu’il pourrait prendre encore quelques années pour que l’on perçoive la croissance du sans-abrisme dû à la récession actuelle, il y a suffisamment de temps pour concevoir, implanter et observer les retombées de nouvelles mesures préventives. Ces nouvelles mesures pourraient cibler des ménages qui risquent de perdre leur logement, ou qui sont nouvellement sans-abris.[1]

- L’impact de la récession variera d’une communauté à l’autre à travers le pays. L’état des marchés immobiliers, des systèmes d’aide financière, et de la planification du sans-abrisme varie à travers le Canada. De plus, les trajets des sans-abris migrant à travers le pays seront difficiles à prévoir au cours des prochaines années. Conséquemment, il sera difficile de prévoir dans quelles communautés et à quel moment surviendra l’augmentation du sans-abrisme. Nous savons par contre que les personnes les plus affectées par la récession de la COVID-19 sont : les jeunes, les femmes, les personnes célibataires et les personnes sans diplôme d’études secondaires.

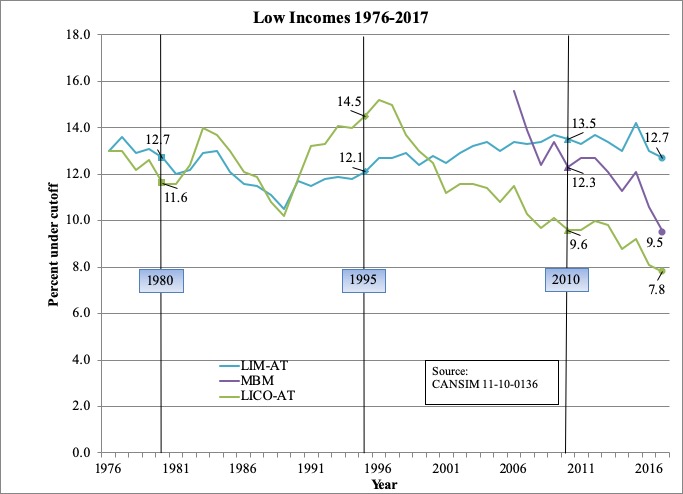

- Afin de tenir compte des nombreux facteurs en jeu, les fonctionnaires doivent surveiller une variété d’indicateurs. Le rapport recommande à EDSC de tenir compte des indicateurs suivants tout au long de la récession : le taux de chômage officiel, la proportion de Canadiens qui tombent sous la Mesure axée sur les conditions du marché (surtout ceux qui tombent sous le seuil de 75%)[2]; les taux d’aide sociale; le cout médian des loyers; le taux d’inoccupation des loyers; la proportion de ménages qui consacre plus de 50% de leur revenu sur l’habitation; les expulsions; et le taux d’occupation quotidien des refuges d’urgence.

- Il faudra faire preuve de nuances avec ces données. Autant que possible, il faudra surveiller l’évolution de ces indicateurs depuis le début de la pandémie, ainsi qu’à travers les différentes régions et groupes démographiques précis (par exemple les femmes, les jeunes, les Autochtones, etc.)

- Le rapport recommande au gouvernement fédéral d’améliorer l’Allocation canadienne pour le logement (ACL). Cette prestation offre une aide financière aux foyers à faible revenu afin de payer leur loyer. Il est prévu que la moitié de cet argent proviendra du gouvernement fédéral, et que l’autre moitié proviendra des gouvernements provinciaux et territoriaux. L’ACL devait être lancée le 1er avril 2020, cependant, il n’y a que cinq provinces qui ont signé l’entente. Le gouvernement fédéral pourrait augmenter son apport à l’ACL afin d’encourager le restant des provinces et territoires à en faire autant. Par exemple, le gouvernement fédéral pourrait offrir d’assurer les deux tiers ou les trois quarts des couts.

- Le rapport recommande également que le gouvernement fédéral fasse preuve de souplesse quant au recouvrement des montants excédentaires de la Prestation canadienne d’urgence (PUC) versés aux prestataires d’aide sociale. Il est nécessaire de souligner ce point vu la confusion considérable entourant le lancement de la PUC. Une telle approche pourrait comprendre un recouvrement partiel chez ces individus (par l’entremise du système d’impôts), et une amnistie totale devrait être considérée dans certains cas.

- Le rapport recommande qu’EDSC mette sur pied une nouvelle source de financement pour le programme Vers un chez-soi (le véhicule principal par lequel le gouvernement fédéral lutte contre le sans-abrisme). Le rapport aborde la réussite d’effets préventifs aux États-Unis à la suite de la récession de 2008-2009, et encourage EDSC à mettre sur pied un programme semblable au Canada. Le programme pourrait mettre de l’avant une aide financière de courte-durée pour les ménages qui sont à risque de perdre leur logement, en train de le perdre, ou qui l’ont perdu récemment. Les cibles pourraient évoluer au fil du temps, à la lumière de changements survenant dans les indicateurs mentionnés précédemment (taux de chômage officiel, proportion des gens avec des revenus inférieurs à la Mesure axée sur les conditions du marché, etc.).

- Le rapport propose des changements politiques que pourraient entamer les gouvernements provinciaux et territoriaux. Ceux-ci comprennent une augmentation des prestations d’aide sociale, de rétablir l’admissibilité des gens disqualifiés de l’aide sociale à cause de la PUC, et encourager les refuges d’urgence à prioriser les solutions basées sur le logement.

En résumé, puisque nous sommes conscients que le sans-abrisme risque d’augmenter au Canada en raison de la récession, les paliers gouvernementaux supérieurs doivent limiter les dégâts. S’ils sont bien conçus, les efforts de prévention du sans-abrisme peuvent être plus économiques que des réponses d’urgences postérieures.

J’aimerais remercier Susan Falvo, Michel Laforge et Vincent St-Martin pour leur appui pendant la rédaction de ce billet.

[1] Il est également très important de continuer à adresser le sans-abrisme existant. J’ai écrit à ce sujet ici (billet en anglais).

[2] Pour d’autres informations par rapport à la Mesure axée sur les conditions du marché, lisez ce billet (en anglais).