Ten things to know about poverty measurement in Canada

Ten things to know about poverty measurement in Canada

Here are 10 things to know.

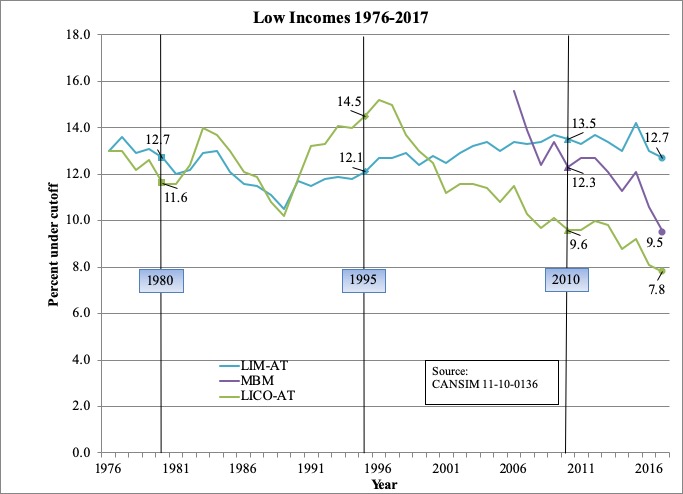

- Use of the Low-Income Cut-Off (LICO) would suggest that poverty in Canada has decreased dramatically since the mid-1990s. LICO focuses on the amount of money spent by a family on ‘necessities’ (i.e., housing, food and clothing) as determined by a group of federal public servants. If a family is spending a substantially higher percentage of their income on such necessities—e.g., 20 percentage points higher than the average Canadian family—then the family in question falls below the LICO. The LICO was supposed to be recalculated on a regular basis to reflect changes in spending patterns, but that hasn’t happened since 1992 and is one likely reason for the reduction in poverty shown by this measure (having said that, the LICO has been adjusted each year for inflation). Today, very few experts take the LICO seriously.

- Use of the Low Income Measure (LIM) would suggest that poverty in Canada has seen mild fluctuations since the mid-1990s. LIM’s focus is on the family’s income, not on what they spend. A family whose income is below 50% of the national median income (adjusted for family size) is said to be poor according to this measure. LIM, in effect, measures income inequality among the bottom half of income earners. The LIM is useful for international comparisons (though it is far from perfect in that regard, as it looks only at income, not the availability of social programs).

- Use of the Market Basket Measure (MBM) suggests that Canada has seen a major decrease in poverty over the past decade. With the MBM, public officials figure out the cost of a basket of goods and services they feel is sufficient for a standard of living “between the poles of subsistence and social inclusion.” Calculations are then made about how much such a basket costs (the cost of this basket has been estimated for 50 regions across Canada). The content of this basket is periodically adjusted, the last time being in 2011, and its value gets adjusted each year for inflation. If you’re poor according to the MBM, it’s because experts believe you could not afford that basket of goods in your community.

Visual courtesy of Kevin Milligan.

- One of the LICO’s shortcomings is that it doesn’t do a good job of accounting for regional variations in the cost of living across Canada. The LICO (as mentioned above) also hasn’t been adjusted since 1992, meaning that it doesn’t currently account for how much things cost today or what people spend money on today (as Andrew Jackson notes, it doesn’t include the cost of Internet). Finally, LICO doesn’t easily allow for international comparisons.

- One of the LIM’s shortcomings is that it can suggest that recessions are good for poverty reduction. As Alain Noël notes, the LIM is “sensitive to changes in the median income, which sometimes produces counterintuitive results. In a recession, for example, when the median income is flat, the poverty rate may seem to be decreasing while unemployment and economic hardship are increasing.” What’s more, the fact that LIM is based on national median income—as opposed to the median income for the province or territory in question—seems arbitrary to many. Indeed, Professor Noël further notes that “real median incomes vary considerably from one province to another.”

- Of the three major indicators, my own preference is the LIM. First, it avoids the inherent challenge of deciding what constitutes an appropriate a basket of goods and services in a country of 37 million people, spanning 10 million km2 and six time zones. Second, I think relativity is what’s really important here—if median income across Canada is increasing, then so too should everyone’s (and vice versa). Third, the LIM lends itself well to international comparisons. I’d like to see it calculated based on national median income for international comparisons, and also based on median income for the economic region in question, in order to provide a more meaningful number.

- The debate within Canada has largely ignored the need for indicators of assets. This point has been made by David Rothwell and Jennifer Robson, who note that income and assets are not always correlated. For example, a low-wage worker might have an income that brings them above the LIM, but they may also have $75,000 in student loans and credit card debt. Conversely, a senior could be relying exclusively on Old Age Security as a source of income while also owning a $2 million home outright. (Monitoring asset poverty might put pressure on provincial and territorial officials to stop discouraging asset accumulation among social assistance recipients.)

- It’s also important to directly measure material deprivation. For example, core housing need measures the affordability, suitability and adequacy of a person’s housing. Likewise, food insecurity measurement directly assesses the inadequacy or insecurity in access to food due to financial challenges. It’s also important to assess who has access to high-quality childcare and prescription medication. (For a critical analysis of the need to directly measure material deprivation, see this 2017 conference paper.)

- In August 2018, Canada’s federal government announced its formal adoption of the MBM as its official poverty measure. Its poverty reduction strategy also unveiled a dashboard of poverty-related indicators. This seems very much in line with a position taken by Peter Hicks in a recent blog post, in which he calls for “an evolving ‘dashboard’ of carefully selected indicators would be more useful than a single measure.” The new federal strategy will use the MBM to monitor progress—importantly, it will not use the MBM to determine program eligibility.

- Seniors make for an interesting case study here. According to the LIM, a great many seniors in Canada currently experience poverty. But according to the MBM, very few seniors in Canada currently experience poverty. As Andrew Jackson pointed out last year: “There is a huge difference between the LIM and MBM poverty rates for seniors (14.3% vs 5.1% in 2015.)” And this raises an important question: if Canada’s official poverty measure suggests there’s very little seniors’ poverty, to what extent will Canada’s federal government prioritize assistance for seniors?

In sum. The Trudeau government deserves praise for unveiling a dashboard of poverty indicators that will hopefully receive close attention from federal officials in partnership with provincial, territorial and municipal officials, as well as researchers and advocates. Having said that, Ron Kneebone reminds me that the MBM has yet to be formally adopted by provincial or territorial governments. There is also reason to be very concerned about what initiatives may or not be in store for seniors, given that the MBM suggests they currently experience very little poverty.

I wish to thank the following individuals for assistance with this blog post: Miles Corak, Filipe Duarte and his students, Susan Falvo, Reuben Ford, Rob Gillezeau, Seth Klein, Ron Kneebone, Andrew Jackson, Marc Lee, David Macdonald, Michael Mendelson, Allan Moscovitch, Geranda Notten, Charles Plante, Saul Schwartz, Richard Shillington, Vincent St-Martin, John Stapleton, Ricardo Tranjan, and Mike Veall. Any errors are mine.