Lifting singles out of poverty in Canada

Lifting singles out of poverty in Canada

I’ve written a report for the Montreal-based Institute for Research on Public Policy making the case for higher social assistance benefit levels for employable single adults without dependants. The link to the report is here.

Here are 10 things to know.

1. In Canada, most employable adult singles without dependants who receive social assistance get less than $10,000/yr. in benefits. This amount of money is ridiculously low (keeping in mind that this figure includes all forms of tax credits received by the recipient). A person with this income must use it to pay for housing, food, transportation and other basic necessities (to see benefit levels in every province and territory, check out Welfare in Canada).

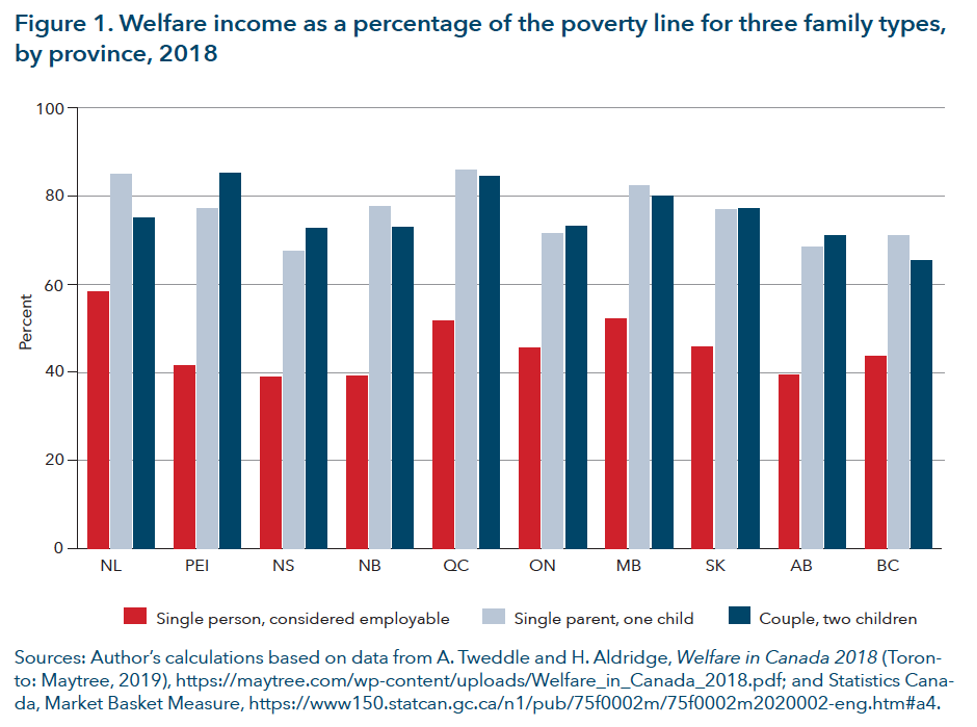

2. In relation to Canada’s official poverty line, social assistance benefit levels for this household group are dismal. ‘Welfare income’—which includes social assistance benefit levels, child benefits and all forms of tax credits—brings couples with two children to between 75% and 95% of the federally-defined poverty line, depending on the province (see figure 1 below). However, welfare income for employable singles without dependants typically comes to about 50% of the poverty line for this particular household type.

3. In most provinces and territories, $10,000 is less than half of what a minimum wage earner would earn in one year working full-time hours. Historically, policy-makers and economists have often been nervous about setting social assistance benefit levels high enough to make paid work unattractive. However, that shouldn’t be a major concern right now in most parts of Canada, as the differential between welfare incomes and minimum wage rates is currently quite substantial.

4. Increases to social assistance benefit levels could help Canada’s federal government achieve its poverty reduction targets. In Canada, we say a household is in ‘deep income poverty’ if it makes less than 75% of the official poverty line. Canada’s Poverty Reduction Strategy, unveiled in October 2018, seeks to track progress on this indicator. Increases in social assistance benefit levels would be a very easy way for progress to be made in this respect.

5. Doing so could also help provincial and territorial governments achieve their poverty reduction targets. All provinces and territories now have their own poverty reduction strategies; many of these strategies include targets pertaining to reducing the number of people under the poverty line (New Brunswick’s strategy actually seeks to reduce deep income poverty by 50%). Increasing social assistance benefit levels would help all provinces and territories achieve their targets.

6. More than half of people in Canada who are in ‘deep income poverty’ are singles. Not only do singles receive very low social assistance benefit levels relative to other household types, but they also do not realize many of the economies of scale that come with cohabitating (e.g., shared rent, shared utility costs, etc.). This reality makes this household group all the more worthy of policy attention.

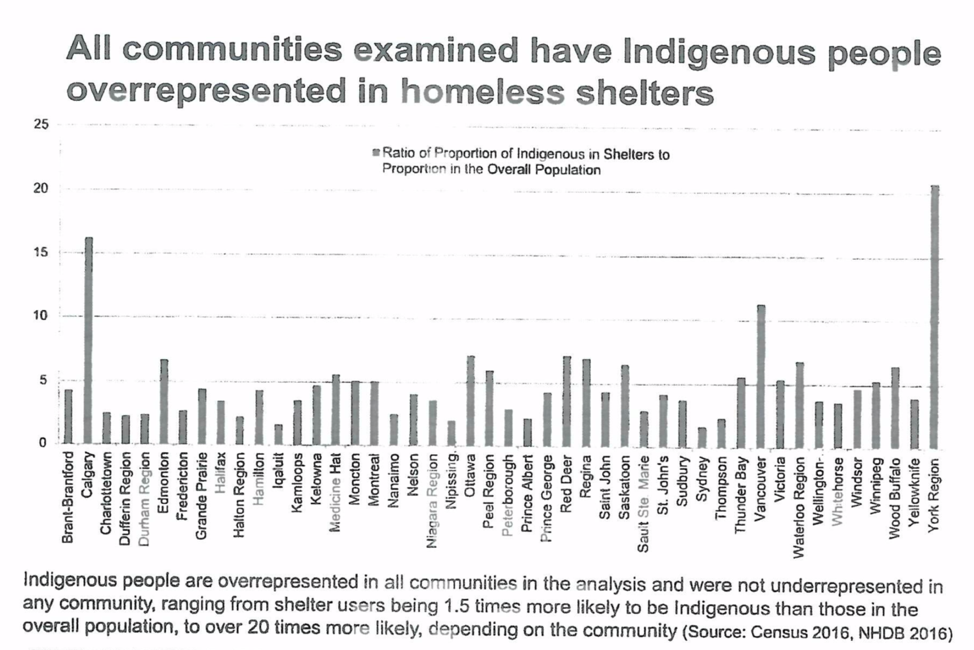

7. Higher social assistance benefit levels can result in less homelessness. It’s intuitive for many of us that higher social assistance benefit levels would both reduce the likelihood of a person losing their housing and also increase the likelihood of a person experiencing homelessness to obtain rental housing on the private market. Research by Ron Kneebone and Margarita Wilkins confirms this, estimating that a $1,500/yr. increase in social assistance benefits for an employable single without dependants would (in 2011) reduce the use of shelter beds on any given night by nearly 20%.

8. Higher benefit levels can improve food security. A recent study in British Columbia confirms this, finding that overall rates of food security improved among social assistance recipients after a one-time increase in social assistance benefit levels in that province.

9. Less homelessness and improved food security would almost certainly result in public cost savings. The costs of homelessness to the taxpayer are well documented, as are the healthcare costs associated with food insecurity. Put differently, increasing public expenditure on social assistance would likely result in public savings elsewhere.

10. While higher benefit levels would likely lead to more takeup, this increased takeup would be modest. That is precisely the finding of a recent Canadian study that I co-authored with Ali Jadidzadeh. We found that a 10% increase in the real value of social assistance benefit levels for this same household group would likely result in an increase in caseloads of less than 5%.

In sum. When it comes to social assistance across Canada, employable single adults without dependants are a very neglected subgroup. Increasing their benefit levels would likely result in less poverty, improved food security and less homelessness.

I wish to thank Susan Falvo, Lynn McIntyre, Vincent St-Martin and Val Tarasuk for assistance with this blog post.